The greatest of love affairs are inexplicable obsessions. In Naushad Ali Khan’s case the object of his undivided attentions is the LP (Long Play), or 33rpm microgroove vinyl record.

He is prepared to go to the ends of the earth for it. Once, he picked up his gramophone and travelled to Umerkot because he had heard a Hindu there owned a Kundan Lal Saigal record that he had been dying to hear. When he reached the gentleman’s house, he informed him that he had come for the record.

“He told me the record belonged to his father and was not for sale and I told him I had only come to listen to it,” Naushad tells The Express Tribune. “He invited me in, served me food, and we listened to [it] around six times.”

When it was time for Naushad to go home, the Hindu told him he was crazy and handed it to him as a gift. The song was Ek Bangla Banay Nyaara from the film President (1937) and today Naushad owns one of the biggest Kundan Lal Saigal collections in Pakistan.

Naushad could have listened to Ek Bangla Banay Nyaara on tape, CD or even online. But as he and other collectors will tell you, vinyl is king. “Vinyl records have the master sound,” he explains simply. “There is a lot of flavour.”

According to the experts, LPs sound better because a vinyl record has a groove carved into it that mirrors the original sound’s waveform. This means that no information is lost as happens with digital recordings on CDs and DVDs. Original sound is analog by definition but digital recordings just take snapshots of the analog signal. As a result, they do not capture the complete sound wave. If you want to listen to the real deal, choose vinyl.

Given technology’s steady march into different, smaller, sleeker more long-lasting formats, most people who listen to digital music can’t really tell the difference. Tell someone you collect records and they will laugh in your face for listening to music on an “ancient” format. Once they’ve stopped laughing they’ll ask if people still even own records.

Their cultural ignorance can be blamed on four decades of change. Records started going out of fashion in Pakistan in what is believed to generally be the mid- to late 1970s. Zeeshan Chaudhry, the general manager of EMI Pakistan, says the manufacturing plants started shutting down around the same time. A more portable format had arrived, giving people a reason to move away from the bigger, unwieldy LP record. Listeners had discovered the cassette tape. Record labels started investing as it was cheaper and handier. Eventually, tape was eclipsed by the compact disc, which was in turn swept aside by the digital.

According to EMI’s Chaudhry, they were the only label in Pakistan and were by default the only ones releasing vinyl. “[People] had a special taste for music back then,” he says. “Their ears were tuned for the good and bad sound.” Over 65 years, EMI released an immense LP catalogue, including notables such as Ahmed Rushdi and Sohail Rana and even a number of obscure Pakistani rock bands no one remembers today.

It was thus Kundan Lal Saigal fans like Naushad Ali Khan who were buying LPs in Karachi those 30 years ago. When he was growing up he had seen people place a mic in front of the gramophone at family functions and the sound had him hooked. His first purchase was a Jesse Green record from Shalimar Recording Company in Saddar and he has been collecting ever since.

Around the time cassette tapes started going big in Pakistan, Naushad happened to move to the UK to play club cricket. As it turned out, this was an LP-buyer’s paradise. His trips to second-hand stores and one-pound shops eventually benefitted people in Pakistan. Every time Naushad would return, he would bring back vinyl and lend them to stores that would make master tapes — one for him and one for themselves to make further copies.

Today Naushad helps manage a weekly market at Sakhi Hassan and buys and sells records and sound equipment on the side. He is the best person to go to in order to track down and purchase records. His network includes over 200 kabarias and extends to Parsis and Christians in Karachi.

Second-hand records are imported by kabarias as parts of lots which also include toys, electronic equipment and books. Naushad gets first dibs on most of the records. His contacts call him each time they get a shipment. In return for this service, he pays for their phone credit.

The phone call is followed by quick trips to warehouses in Gulbai and Shershah to sort through records he would want. But the sellers insist he buys in bulk. So some days even though he may only want to buy four out of a lot of 200 records, he’ll have to buy all of them at Rs30 per LP.

“One time I found Are You Experienced? by Jimi Hendrix in a lot of 79 records,” says Naushad. “I offered the guy Rs300 for that [one] record, but he said I’d have to buy all of them for Rs7 each.” He ended up keeping on 13 records and gave the rest away. Michael Jackson and Barbara Streisand really aren’t really his cup of tea.

If you ask Naushad for his favourite records, he will bring out a bag with a lock and carefully open it. Nestled inside are original Jimi Hendrix releases. “These and all of my blues records are my most prized possessions,” he says.

As vinyl disappeared so did some names. One of them is Mairaj who will invariably be mentioned in any conversation you have with a record collector. He owned a store in Khori Gardens where he would sell records and other sound equipment.

But after his death, all you will find are a few scratched records stowed away at the back as his sons sell plastic and tent materials.

Collector Faisal Gill used to buy from Mairaj. “People would leave their records with Mairaj and we would go and buy them,” he explains. “There were others as well, Mansoor near Regal Chowk, Ghafoor in Ghaas Mandi. A lot of people bought their records from these guys.”

Faisal Gill is a bit of a legend himself in this world. The sound therapist, who works with children with special needs, has been buying for over 20 years and while he has lost count a rough estimate would put his collection at 6,000. His first records were handed down to him by his father and the first record he bought was a German compilation of pop music.

When stores selling tapes started clearing out their records to make way for more cassettes and CDs, Gill was one of those who picked up most of their libraries. “I purchased records from Scanners and Virgin,” he says by way of example.

And as records became harder to find in the markets and secondhand markets became inaccessible, collectors closed rank. It is through these circles that they buy, sell and trade records. So, for example, a collector might get word of a wanted record available at someone’s house and will just show up to request a sale or trade.

Now most of the purchases come from abroad, and Gill says he doesn’t have the time to run after sellers and sort through the lots. But if you’re lucky and your network isn’t as strong, you can still definitely find some gems at the weekly markets in your city.

In Islamabad, for example, an Indian correspondent, Rezaul Hasan Laskar, who started his career as a music journalist, has had plenty of good luck while he worked there for roughly five years before returning home recently. He began collecting vinyl when he moved to Pakistan. “My wife would go to the [lunda] bazaar and I never had the time to,” he says. “One day she said you have to come check it out and I started going with her on weekends. It was crazy! I picked up my first LP player for Rs400 and a number of records from classical to rock and roll.”

Over time the seller got to know Laskar and would call him every time a new shipment would come in. This way he’d get to pick records before anyone else did. But the records weren’t always clean. “Sometimes you pick up stuff that doesn’t play or is too badly scratched and sometimes you pick up pristine copies,” he said.

Prices in Islamabad are lower than in Karachi. In the capital you can buy a record for Rs20 at the bazaar and for Rs100 at stores. Sellers in Karachi are, however, slightly more savvy and can go as high as Rs2,000 for a record. But as you can imagine, if it is a rare LP of The Dead Kennedys, there’s probably no limit to how much you will pay.

With information from Discovery Communications Website Howstuffworks.com

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, July 14th, 2013.

Like Express Tribune Magazine on Facebook, follow @ETribuneMag on Twitter to stay informed and join the conversation.

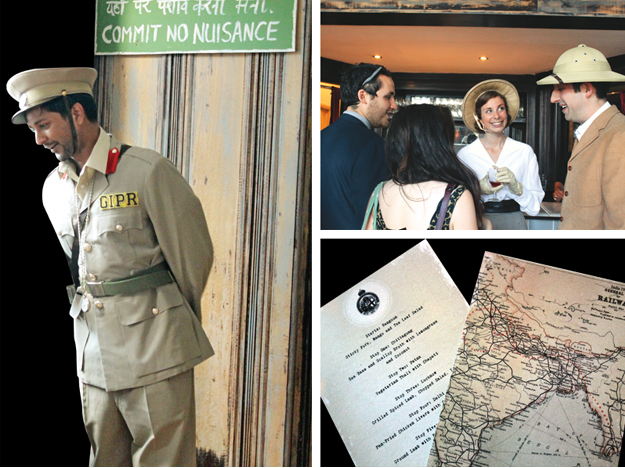

At the Muslim Charity fund-raising dinners in Manchester, Birmingham and London May 31 to June 2, 2013. PHOTO: MOHAMMED RAYAZ

At the Muslim Charity fund-raising dinners in Manchester, Birmingham and London May 31 to June 2, 2013. PHOTO: MOHAMMED RAYAZ

At the Muslim Charity fund-raising dinners in Manchester, Birmingham and London May 31 to June 2, 2013. PHOTO: MOHAMMED RAYAZ

At the Muslim Charity fund-raising dinners in Manchester, Birmingham and London May 31 to June 2, 2013. PHOTO: MOHAMMED RAYAZ

Junaid Jamshed and Ali Haider performing at the Spiritual Chords Nasheed concert held in South Africa in August 2011. PHOTO: MUSLIM CHARITY SOUTH AFRICA

Junaid Jamshed and Ali Haider performing at the Spiritual Chords Nasheed concert held in South Africa in August 2011. PHOTO: MUSLIM CHARITY SOUTH AFRICA Junaid Jamshed helped raise funds for the charity that was involved with the building of Doha village in Sanjarpur, Rahimyar Khan. PHOTO: MUSLIM CHARITY

Junaid Jamshed helped raise funds for the charity that was involved with the building of Doha village in Sanjarpur, Rahimyar Khan. PHOTO: MUSLIM CHARITY

Source: Deutsche Himalaya Expedition Map of Nanga Parbat, Pakistan Trekking Guide by Isobel Shaw and Ben Shaw. ILLUSTRATION: JAMAL KHURSHID

Source: Deutsche Himalaya Expedition Map of Nanga Parbat, Pakistan Trekking Guide by Isobel Shaw and Ben Shaw. ILLUSTRATION: JAMAL KHURSHID